Prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil in the 16th century, there were over 2,000 Indigenous tribes (centered around four major language families) on the land, which numbered nearly 11 million in population. Similar to patterns of colonization from the Europeans in North America, many of the Indigenous peoples were killed due to contact with European disease or brutal enslavement practices. There are currently an estimated 1.5 million Indigenous people in Brazil.

According to The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed. 1999) the Indigenous peoples of Brazil were centered around four language groups: Tupi-Guarani (situated along the Atlantic coast), Ge (central plateau), Carib and Arawak tribes who were situated in the Amazon basin.

Initially, when the Portuguese arrived they had little long-term interest in Brazil. The Portuguese were expanding in North Africa and more interested in the Asian trade routes. They also did not have the military and settlement resources as did the Spanish, English and French (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed. 1999). Accordingly, Portuguese ventures were mostly invested in exploiting commercial interests and returning to European lands. The inhabitants were not of interest because they did not wear jewelry of gold or silvery and did not seem lucrative for material benefit. The Portuguese did not think they had anything of material value to gain from interaction with natives. Instead, the Portuguese focused on trade based on local resources (monkeys, Indian slaves, parrots, dyewood) (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed. 1999).

However, this strategy progressively changes with the advent of sugarcane and the realization of just how lucrative a commodity sugarcane actually was – this actualization is dated to the first decades of the 16th century. The rise in demand for sugar cane came in time with the decline of the East spice trade. There is a direct correlation between the change in perspective on Brazil and the rise of colonial intent by the Portuguese, who established their royal government in Bahia in 1540.

At this point, the Portuguese Crown gave the royal government permission to expand their presence in Brazil through the building of forts and the pacification and conversion of Indigenous peoples. Initial attempts failed but the Jesuits moved the Indigenous populations from their land to fortified villages in order to complete conversion (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed. 1999).

The Barra Lighthouse pictured below was the first fortification in the country

The Barra Lighthouse in Bahia was visited by the USYA participants. The lighthouse is also home to the Nautical Museum of Bahia.

Seeing the lighthouse, you simply can’t ignore its majesty, however, just as we saw in many beautiful historical sites – there is deeply profound tragedy within the walls.

This is the first Portuguese fortification in Brazil and within the walls, the story of European conquest and enslavement is documented.

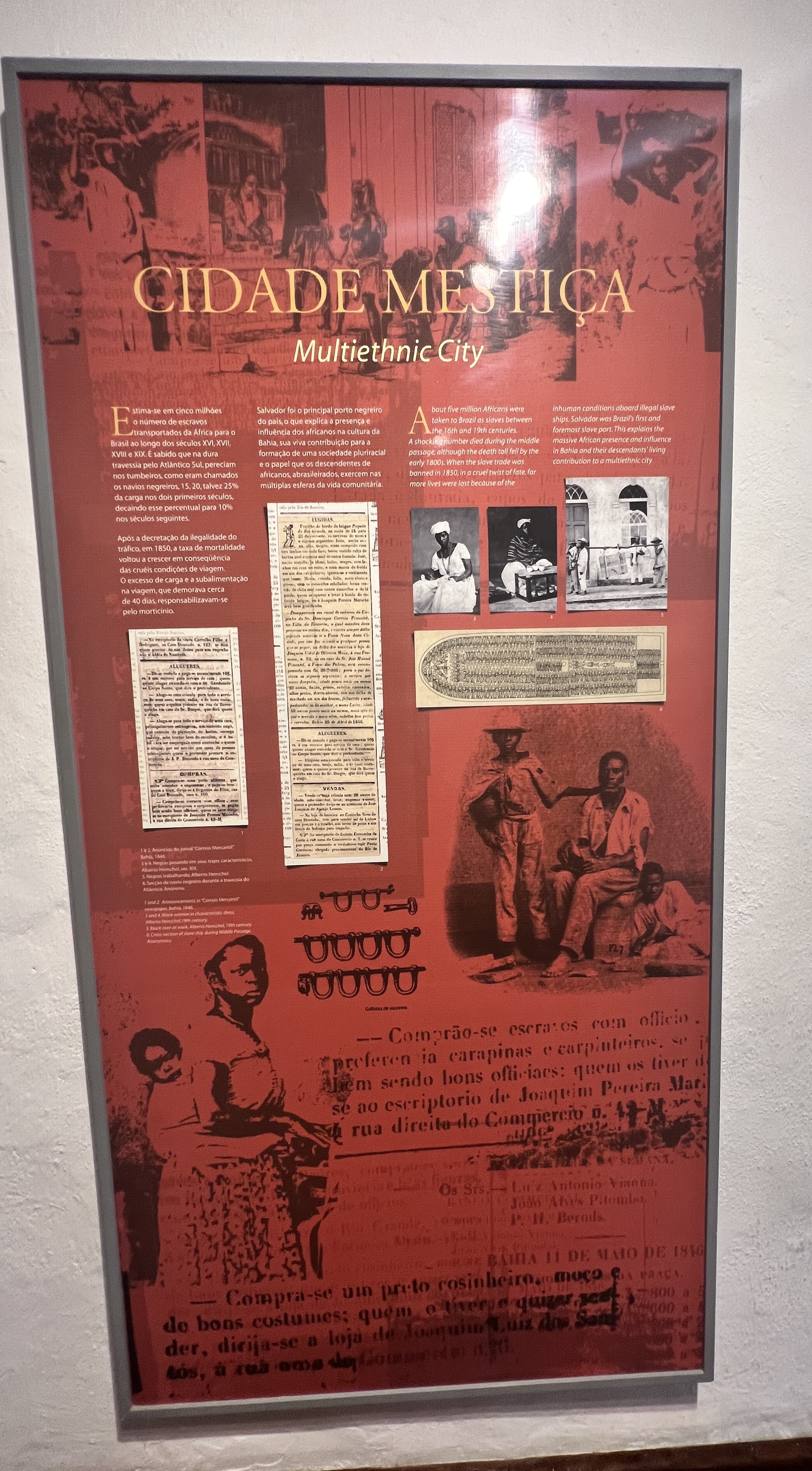

The images from left to right: our tour guide Luan (IG @dhoug_), a replica of slave deck which was designed to transport as many humans as possible, a poster on the multi-ethnic nature of Bahia due to the slave trade and finally, the last photo is of our amazing translator, Julia Soares and a Barra Lighthouse guide.

Remember, initial development in Brazil was based on agriculture until the discovery of gold. “The eighteenth century gold rush did, however, spur public works, church building, and urban development” (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed. p. 14). This also changed the scope of Portuguese colonialism in Brazil. During its colonial period a staggering two-thirds of the inhabitants of Brazil were enslaved (R. Levine, J. Crocitti, Ed., 1999).

The Catedral Basilica de Salvador, or what is known as the Golden Church is a testament to the wealth and power the gold rush gave to the Portuguese, along with the importance of Catholicism in the colonial territory.

The church took 18 years to build using slave labor and is central to Pelourinho (Salvador’s Old City). This church was simply breathtaking in its extravagance.

USYA participants also visited the Church of Our Lord Bonfim. In addition to Catholic beliefs, you’ll notice ribbons everyone. These ribbons indicate a wish someone has made – you make a wish, tie the ribbon on your wrist or ankle and once it falls off the wish, according to superstition, will come true.

The ribbons give the church another layer of meaning as they are the visual representation of so many individual wishes.

Every ribbon is a hope, dream, or aspiration.

In addition to the construction of churches, the Portuguese spear headed construction of the first urban elevator, known as Lacerda’s Elevator.

There are no spectacular views within the elevator itself but you can see from the photos below that it connects the upper part of the city to its commercial district. The image on the left is the view from the top portion of the city, before getting on the elevator. The image on the right is from the commercial district.

The buildings below are located in the historic center of Salvador, within the UNESCO World Heritages.

The above image is the former seat of government in Bahia, one of the first palaces built in Brazil which dates back to 1549. The architecture of the Old City follows closely the Portuguese Baroque style architecture.

In essence, colonialism, Catholicism and the architecture of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil are integrated in a way that serve as reminders of the power, influence and cultural transformations. The palaces remain, although they do not serve the same function (the tour guide mentioned the possibility of one of the palaces being acquired and developed by a foreign corporation as a hotel), they serve as a constant reminder of physical and spiritual conquest.

Levine, R, & Crocitti, J. (Eds.). (1999). The Brazil Reader History, culture, politics. Duke University Press.

This website is not an official US Department of State website. The views and information presented are the participant’s own and do not represent the United States Youth Ambassadors Program, the US Department of State, or World Learning.**